In the spring of 2022 I walked from Leeds, Yorkshire, in the north of England, to Canterbury, and then to Dover: a total of 720 kilometres, in 28 days. Along the way, I discovered that walking in England is quite different from walking the pilgrimage routes of Italy, France and Spain!

Why start in Canterbury?

I first walked on the Via Francigena in 2015, from my home in the Italian region of Liguriato Rome. Then in 2021 I joined “Via Francigena. Road to Rome 2021 – Start again!” to walk from Rome to the very end of the Italian peninsula, Santa Maria di Leuca.

But I was missing all of the Via Francigena north of where I live, so that seemed the logical route to walk next!

The Via Francigena begins in Canterbury… but why begin there? Canterbury Cathedral has itself been a pilgrimage destination ever since the martyrdom of St. Thomas à Becket in 1170, as famously reported by Geoffrey Chaucer in Canterbury Tales: “from every shires ende / Of Engelond to Caunterbury they wende / The hooly blisful martir for to seke / That hem hath holpen what that they were seeke.”

My own personal pilgrimage from the north of England

The pilgrims of Canterbury Tales set out from the Tabard Inn in Southwark, but I personalised my pilgrimage by beginning in the city of Leeds, where I was born, and specifically at the address appearing on my birth certificate. It took me 26 days to “wende” my way from there to Canterbury, and another two days from Canterbury to Dover: a total of 750 kilometres. The route I followed is St. Bernard’s Way, mapped out by Tony Maskill-Rogan in 2014 between Rievaulx Abbey in North Yorkshire and Citeaux Abbey, south of Dijon in France.

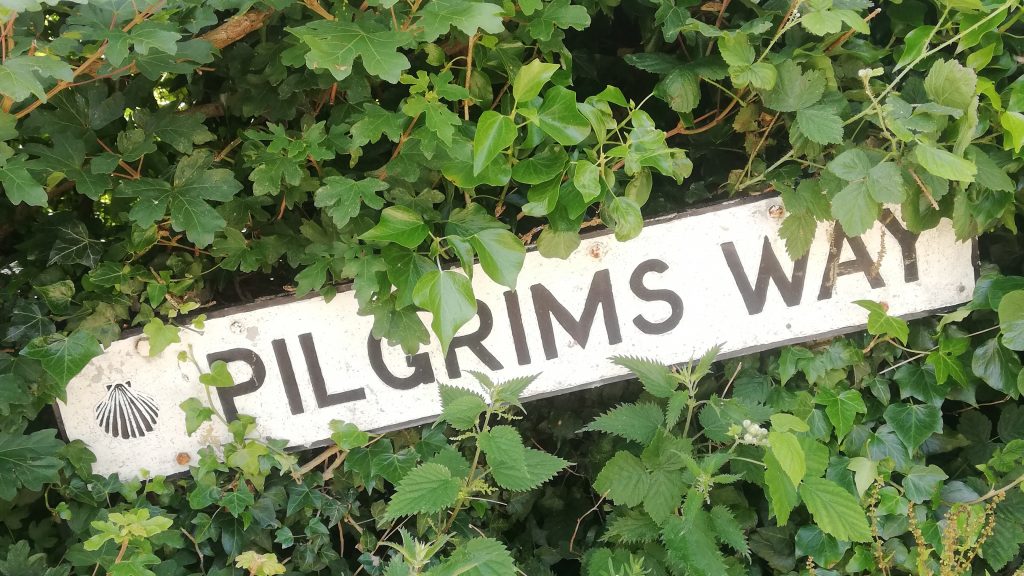

After Canterbury, the route follows the Via Francigena. But north of Canterbury, this is not a commonly walked route; in fact, I found no record on the internet of anyone else having walked it since Tony mapped it out in 2014. But Tony put together the route using existing footpaths, and they were all still there; I had to make only one major diversion due to new construction, and that was well-marked because it was part of the Trans-Pennine Way, a popular cycling and walking route.

This route turned out to be perfect for my own personal pilgrimage, because it passed through the hometown of my grandparents and my great-grandparents!

But my family history is not the subject of this article, in which I would like to offer long-distance walkers a few pointers about walking in the UK in general, as compared to walking the pilgrimage routes of Italy, France and Spain.

A long tradition of walking, and public right of way

Walking is a popular pastime in the United Kingdom, and the people I came across on my way understood the concept of long-distance walking, even though I only met two long-distance walkers whose route intersected mine: all the other people I met on the footpaths were out jogging, or walking their dogs.

But what really makes walking in England different is that walkers enjoy more rights in Britain than in continental Europe. Anywhere where there is an established footpath, walkers have the right to pass, even on privately owned land. The owner of the land is required to keep the footpath open, accessible and clear of vegetation at all times. Most farmers clear a track right through the middle of their fields using herbicide, producing a striking yellow line across the green fields of wheat!

If there is a fence, there must be an openable gate, or a stile: steps allowing people to climb over the fence while preventing animals from crossing.

Right of way across private land is a major plus for walkers! In the course of my 750 km walk I found myself walking across countless farmers’ fields, as well as through the park of a privately owned noble estate, across a fully operational airfield, and even across a golf course: I was perfectly entitled to be there, as long as I stayed on the marked public footpath. The golfers even paused their game to let me pass through safely!

Bull in field

Farmers in Britain are obliged to keep footpaths clear of vegetation – but not clear of animals. Before crossing through a gate or over a stile into a new field I always scanned the field for livestock.

Sheep were never a problem, because they don’t come with shepherd dogs in England, as they do in Italy. Dogs in general are not a problem in Britain, at least in my experience! They are very well-behaved and rarely even bark at walkers passing by.

But cattle I am not so fond of! Before entering a field of cattle, I always took a good look to make sure none of them were bulls. The farmer is supposed to put up a “Bull in field” warning sign… but sometimes the sign was on the opposite side from where I entered the field. And other times the sign was there, but there was no bull in sight.

I found that the best policy was to take a good look, and if there was a bull in the field, I attempted to find an alternate way around.

Young cattle are also a problem: most likely not dangerous, but rather annoying! On one occasion I clambered over a stile into a field that appeared to be empty, only to discover a herd of twenty or so young heifers and bullocks that had been hidden around the corner of a farm building. As soon as they spotted me, they all came trotting over to take a closer look, and decided it would be amusing to accompany me across the field!

The young cattle found it entertaining to see how close they could get to me before I shook my sticks at them. I tired of this game before the pesky teenaged cattle did, so I ducked under a barbed-wire fence into the next field… only my backpack caught on the barbed wire! Attempting to free a snagged backpack from a barbed wire fence while a dozen or so feisty young cattle sniffed at it would have made an amusing spectacle, if there had been anyone else around to watch!

Hedgerows

In Britain, farmers’ fields are traditionally separated by hedgerows. The problem with these is that the margin of error involved in following a GPS track means you may sometimes end up on the wrong side of a hedge. If you miss a gate hidden by branches and continue along the hedgerow to the bottom of the field, you may find another hedge across the end of it, preventing you from getting out of the field and continuing on your way. This happened to me a few times, and I had to backtrack; it’s pretty much impossible to squeeze through a hedge with a backpack and poles!

Nettles

Poison nettles are not an issue when walking in the south of Europe, where they only grow as high as your ankles, and only in particularly damp and shady spots. But as Britain is damp and shady practically everywhere, it has super-nettles that grow to shoulder height and sting right through your clothes! The secret to getting through a particularly overgrown patch is to put on your waterproof jacket and trousers: nettles don’t sting through plastic!

Weather

The British are famous for talking about the weather, and there is a good reason for that. They actually have weather, and it changes, not only every day, but several times during the day! Be prepared for anything from scorching heat to driving wind and steady rain when walking in the UK.

And remember that commenting on the weather is the perfect way to strike up a conversation with anyone you meet along the way!

Public transportation

Britain may at one time have had reliable and affordable public transportation, but it doesn’t anymore. Theoretically, this should not be a problem when undertaking a Long Walk, but it can be if, for instance, you have trouble finding accommodations at the end of a stage and need to skip ahead or back for the night!

I made the mistake of booking two nights at the same hotel, because it was particularly affordable, then walking 12 kilometres and attempting to call a taxi to get back. “Sorry, we can’t pick you up there – you’re outside of our zone,” was the reply. Luckily someone nearby overheard the conversation and offered to give me a lift to the nearest town, where I could catch a bus. To get back to the same spot and start walking there the next morning, I had to take three buses, a total of one and a half hours, paying for a separate ticket for each bus because they were all run by different companies – to travel to a point only 12 kilometres away!

Roads

For some reason I was under the impression that British motorists have a lot of respect for pedestrians. I couldn’t have been more mistaken!

Pedestrian crosswalks, despite the iconic Abbey Road image, are few and far between, at least outside of the major cities. Even where a well-established footpath crosses a road, you will need to wait, and watch, being careful to look in the right direction, and make a dash across the street! And be very, very careful if you are tempted to take a shortcut along a road, rather than following the established footpath: British country roads are narrow and winding, with no sidewalk or shoulder, and have those annoying hedges along each side. There may be a metre of grass between the road and the hedge, but it is not designed to be walked on, so the grass may be long and full of nettles, and there may be uneven ground beneath it. I soon learned to check out the route on Google Street View before booking accommodations that would require me to leave the footpath and walk any distance along a road.

Accommodations

As the route I was walking was not a recognised, well-travelled pilgrimage route, there were no inexpensive pilgrim accommodations available. For each stage, I had to research the availability of accommodations and food close to my walking route by loading the GPS track into Google Maps and looking at what facilities were available along the path. I paid the going rate for a single room at hotels and Airbnb’s. Luckily, for a few nights I was hosted by friends, and I also managed to find hosts through Servas International, forging new friendships along the way. In fact, I quite enjoyed the challenge of finding accommodations along the way, and the variety of solutions added interest to the trip: from an Airbnb bedroom in a big old farmhouse to a historic railway station hotel, from a self-contained shepherd’s hut in a field to a university convention centre, from an upstairs bedroom in the home of a Jamaican immigrant to a room above a pub.

Food… and the ubiquitous kettle!

Restaurants are expensive in the UK. Pub food is cheaper, and if the pub also has rooms for rent, this is the ideal solution: you only need put on your slippers to come downstairs for dinner, and beer!

Whatever your accommodation, if it includes a “Full English” breakfast, you can be quite sure you won’t be needing lunch!

Failing that, tea rooms are an excellent option for a late breakfast, a lunch, or a snack at any time of day, serving inexpensive sandwiches, sweets, and, of course, tea. They can often be found at attractions such as churches, parks, and heritage sites.

To save money and eat a healthier diet, go to the grocery store: British supermarkets sell a variety of ready-made dishes, to be simply heated up or eaten just as they are, and their quality is quite acceptable. In some small towns I found a “community shop” and tea room, run by volunteers as a public service. Some of these are even unstaffed, and rely on an honour system to collect payment.

A big bonus in British accommodations is that they invariably provide a kettle. Whatever kind of room you rent, it will come with teabags, pouches of instant coffee, possibly even hot chocolate powder and biscuits…. And a kettle. This simple appliance vastly expands the range of potential dine-in options: instant noodles, cup-a-soup, instant oatmeal…. The possibilities are endless!

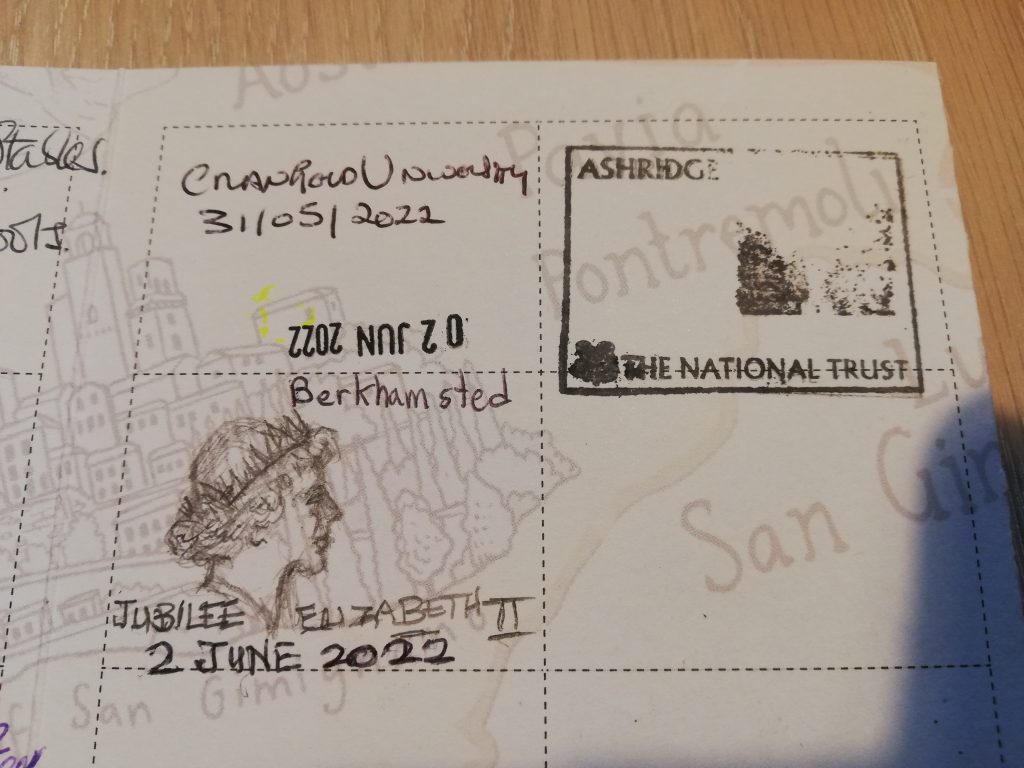

Stamps

If you go about asking for a stamp in England, you will be directed to a post office. No-one north of Canterbury is familiar with the concept of stamps on a pilgrim passport! And businesses don’t have a stamp, like they do in Italy, where, if all else fails, you can settle for a business stamp bearing the name, address and tax code of a hotel, bar or restaurant on your pilgrim credential as a record of your passing. In England, I often asked the people who hosted me to write the name of their establishment and the date in the little square on my pilgrim credential, or to draw a little picture.

Not even the churches I stopped at had a stamp, but if I could find the vicar, I would ask for his or her signature. I even obtained the signature of the Bishop of Newcastle, who happened to be giving a guest sermon in a church I stopped by one Sunday just north of London!

A good reason to go to church!

On the plus side, when the Sunday service ends in a British church, the congregation has coffee and cake in the parish hall next door, or right there in the nave! A few times I managed to drop by a church just as the Sunday service was ending – just in time for coffee, cake and the vicar’s signature on my pilgrim credential.

One place where you can find stamps in Britain is at National Trust heritage sites. The National Trust sells its own “passport” in which people can collect stamps from the various heritage sites they visit, and the staff are happy to stamp pilgrim passports as well!

Summing up the pros and cons of walking in Britain, as compared to walking in Italy, France or Spain: the inconvenience of shoulder-high nettles, curious cattle, and the unavailability of pilgrim hostels or stamps is more than compensated by the existence of a “culture of walking” that goes back a couple of centuries to the days of the great Romantic poets. This means that walkers in Britain have rights they do not have on the continent, and are understood, and welcome, wherever they go!